Diverticular Disease Of The Colon

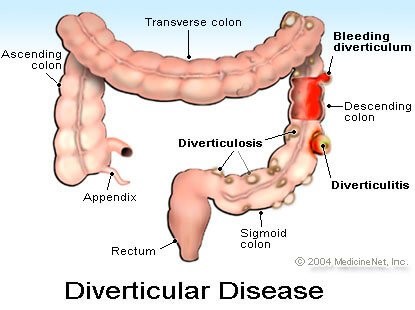

A healthy colon is a smooth tube-like structure that is internally lined by a layer of epithelial (surface) cells. The walls of the colon contain muscles, along with many small penetrating arteries that pass through the muscular wall of the colon to carry blood to the inner layer of epithelial cells. The final part of the colon is called the sigmoid, where the colon is at its narrowest.

The colon forms the final portion of the intestinal tract. Food is mostly digested in the stomach and small intestine and the residual material takes about 18 to 36 hours to journey through the colon. A few remaining nutrients and much of the water is absorbed in the colon, which is about 1,5 meter long.

Aging causes thickening of the walls of the colon, making the colon narrower in certain areas, causing the colon to work harder to push the contents along. Stools that are overly hard or dry due to lack of fiber and not enough liquids in the diet, can add to the pressure in these areas. Over time the increased pressure can cause weak areas in the colon’s inner wall to bulge outward to form small pouches, called diverticula.

Diverticula can appear anywhere in the colon but tend to form more on the descending side of the colon. They are usually about the size of a pea but can be larger. This condition is called diverticulosis and the person is usually not aware of the existence of the diverticula. However, the diverticula can become inflamed, a more serious condition called diverticulitis. (The “itis” refers to inflammation.)

Symptoms of diverticulosis:

People are often not aware that they have diverticulosis, as it usually does not cause any symptoms. A colonoscopy or CT scan for unrelated health conditions are often the first time that the condition is discovered. Symptoms may show up as mild cramps, bloating or constipation.

Symptoms of diverticulitis:

About 10% of people with diverticulosis can develop the more serious diverticulitis when some of the diverticula become inflamed or infected. The most common symptoms are abdominal pain, fever – sometimes accompanied with chills, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, constipation or diarrhea, and bright red blood in the stool. Diverticular bleeding, also called rectal bleeding, occurs when a blood vessel near the diverticula bursts. Pain, usually on the lower left side of the abdomen where the descending part of the colon is situated, is the most common symptom and can come on suddenly or start out mild and increase in severity over several days.

The uncomplicated type of diverticulitis is a condition where the infection or inflammation is mild and confined to the colon. The more serious type of diverticulitis is referred to as complicated diverticulitis.

Complicated diverticulitis typically results from a tiny perforation in the wall of the infected or inflamed diverticular sac, which allows bacteria (hundreds of millions are packed into feces) to infect the surrounding tissue. Usually, the body’s immune system confines the infection to a small area outside the colon. In severe cases, the infected area outside the intestinal wall can enlarge to become an abscess, or even lead to infection and inflammation of the membrane that lines the inner abdominal wall, a condition called peritonitis.

Complicated diverticulitis can cause a perforation in the intestinal wall, which can result in the bowel contents spilling into the abdominal cavity. Complicated diverticulitis can also cause a fistula, which is an abnormal connection between the infected part of the colon and adjacent organs, such as the bladder or other parts of the intestine.

Treatment of diverticular disease:

As diverticulosis is unlikely to have symptoms and may not need treatment, eating a diet high in fiber is a good preventative measure to ensure the condition does not deteriorate into diverticulitis.

Mild diverticulitis is usually treated with an antibiotic, but severe diverticulitis may require hospitalization for treatment or surgery.

Prevention of diverticular disease:

Diverticular disease can be prevented by having regular bowel movement and by avoiding constipation and straining. This can be achieved by eating more foods that are high in fiber, as fiber helps to make the stool bulkier, softer, and easier to move through the colon, which reduces pressure in the colon.

A diet without enough fiber, such as consuming lots of refined carbohydrates, means the stools are hard and small. As a result, the colon contracts with more force to expel them, meaning extra pressure on the wall of the colon. This extra pressure is highest where the diameter is smallest, leading to diverticular pouches forming more frequent in the narrow sigmoid area of the colon.

There are two types of fiber – soluble and insoluble fiber – and you need both kinds for optimal digestive health, says Harvard. Soluble fiber attracts water in the stomach to turn into a gel-like substance, which aids feelings of satiety, while softening the stool. Examples of food with soluble fiber are oat bran, lentils, peas, beans, seeds, nuts, and some fruit and vegetables. Insoluble fiber does not dissolve in water and adds bulk to the stool, which helps to prevent constipation. Insoluble fiber is found in foods such as wheat bran, whole grains, dried fruit, and the skins of fruit and vegetables.

Fiber helps the body to absorb nutrients from food and plays a role in lowering LDL cholesterol.

Being overweight is one of the risk factors for diverticular disease and a high-fiber diet can assist with weight loss, as fiber helps to make you feel full more quickly and can prevent overeating. Smoking is another risk factor, with studies indicating a 36% higher risk of diverticular disease for smokers than for people who have never smoked. Some types of medications are also associated with a higher risk of diverticular disease, such as steroids, opiates (narcotic pain medication), and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

As fiber absorbs more water, drinking plenty of fluids together with a high-fiber diet helps to promote normal bowel function and helps to keep the stool soft and on the move.

Physical movement from daily exercise increases the passage of food through the intestinal tract.

Inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome:

Inflammatory bowel disease refers to the lining of the digestive tract being chronically inflamed and irritated, due to a malfunction of the immune system. It is characterized by two conditions:

- Ulcerative colitis, which affects the colon and the rectum.

- Chron’s disease, which can occur anywhere in the digestive tract.

Irritable bowel syndrome refers to a condition where there is no obvious inflammation in the digestive tract, but the symptoms may be the same as for people with inflammatory bowel disease. As there are no obvious signs of inflammation, it is suspected that the condition may result from uncoordinated intestinal contractions, which can affect bowel movements, and from hypersensitive nerves in the gut, says Harvard.

Conclusion:

Dysfunction along the long and winding digestive tract can play a role in how well nutrients are absorbed from food and how well you fight off disease.

Studies have found that fiber is your best weapon against diverticular disease. The best way to avoid diverticular disease is to follow a high-fiber diet, maintain a healthy weight, get adequate exercise, and maintain a healthy, diverse microbiome by adding probiotics to your diet.

References:

Diverticulosis and diverticulitis. Harvard Medical School Guide. Copyright 2018. (www.health.harvard.edu)

Diverticulosis and diverticulitis of the colon. Published online and reviewed 1 April 2020. Mayo Clinic. (www.mayoclinic.org)

Diverticular disease of the colon. Published online and reviewed August 2018. University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. (www.uihc.org)

Diverticular disease of the colon. Published online and updated 29 August 2020. Harvard Men’s Health Watch. Harvard Medical School. (www.health.harvard.edu)

Are inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome the same? Published April 2021. Harvard Women’s health Watch. Harvard Medical School. (www.health.harvard.edu)

HEALTH INSIGHT